A couple weeks ago, I was walking with a friend, when she abruptly stopped listening to me and turned to look at a bulletin board we were passing. I followed her gaze, and… oh. Uh. Wow.

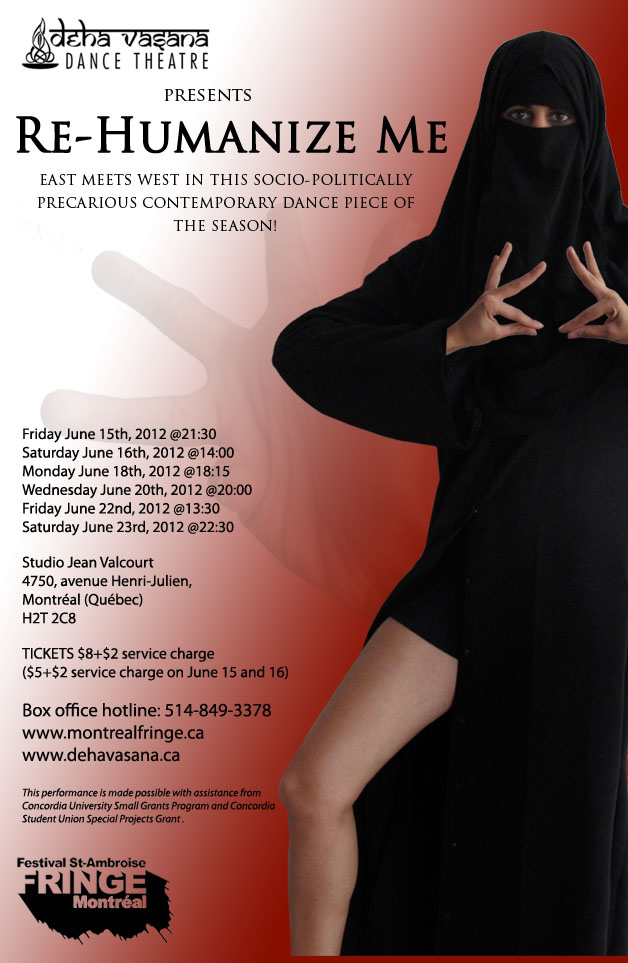

Advertising a contemporary dance theatre performance called “Re-Humanize Me” at Montreal’s Fringe Festival, the poster features a woman in niqab in an Indian dance pose – with one bare leg peeking out from her abaya. When I looked up the performance online, I found the postcard image (see below) as well, which is similar, but with both legs exposed, bent, and turned out.

The description on the Montreal Fringe Festival website says:

“DISCLAIMER! Socially controversial. Politically precarious. Intriguingly risky discourse. Re-Humanize Me exposes flaws in a multicultural society and begs reflection on perceptions of the body from different cultural angles. Do we take advantage of what we are familiar with? This captivating performance will turn heads in every direction.”

I’ll get to the performance in a second, but let’s stop and talk about the publicity, and the posters/postcards especially. The title suggests that this performance is something that will “re-humanize” (presumably at least in part referring to re-humanizing women who actually wear niqab), and the website description paints it as “controversial” and “risky.” Of course, those quotes are referring to the performance and not to the promotional material, but the publicity still forms part of the overall project, and I think the images fall short of the project’s goals. On one hand, given the long history of Orientalist imagery of the seductive, partially-veiled, exotic Arab and/or Muslim woman, there is nothing particularly new or daring about showing a woman in niqab in this kind of pose.

So, as far as the images go, “risky”? Not so much. “Controversial”? Maybe, but oh so tired and overdone.

And “re-humanizing”? Nope. First because, again, these images fall into a long history of images that have been used to sexualize and objectify Muslim women. And secondly because, well, what’s being said if the way to “re-humanize” women who wear niqab is to show some skin? Why is there always this need to go “behind the veil” in order to “understand” (or humanize) women who cover certain parts of their bodies?

On a simple publicity level, the poster obviously worked, because it got my attention and actually led me to go to the show, even if that was initially out of a reaction to how problematic I thought the poster was. (In fact, six friends came with me! So yeah, very successful in getting attention, even if it wasn’t fully positive attention.) But insofar as the poster is part of this project of “re-humanization,” it seems pretty counterproductive.

I’ll move on to the performance itself now, with the caveat that contemporary dance is not something I know much about (my tap dance background is useless here, I’m afraid), so I can’t say a lot about the quality of the actual dancing and movement, although this review gives a brief overview of that aspect. Overall, I found parts of it really compelling to watch, but for much of the show I was paying more attention to the audio track, which seemed to do more in getting the points across than a lot of the movements on stage.

Choreographed by Alida Esmail of Deha Vasana Dance Theatre, “Re-Humanize Me” consists of two women (Esmail herself, along with Aditi Dixit). The show begins with the two women standing onstage, in niqabs and abayas, as we hear a collection of radio news reports and interviews about niqab, and specifically about the ways that it has been discussed in politics in Quebec over the past few years. These audio montages return a few times throughout the show, and reflect voices of women who wear niqab, and others arguing for the right to wear it, as well as Muslims arguing against the niqab, and various arguments made about the place of niqab in Quebec society. When the first audio piece ends, and the women remove their outer clothing, leaving them in sports bras and shorts (see images here). The rest of the performance includes them frantically looking through and scattering piles of newspapers; a particularly powerful image is when one of the women is lying down and completely covered by newspaper pages, showing the power of media images on her body. Later, the women find themselves back in niqab; each of them starts dancing, while the other stops her periodically to fix her clothing, which keeps revealing faces, hair, legs (although the legs never end up fully covered, as in the poster, and my criticisms of the poster apply here too). The focus in this section seemed to be on how those in favour of niqab work to police women’s bodies. At the end, they dance together, to music, and still in full niqab; the show ends with the women dancing, a man appearing on stage, and sounds of gunshots as the stage goes black.

There’s a very short version of the play in this video; it’s not exactly the same as what I saw, but it gives you a general feeling for what it was:

I spoke briefly to Alida Esmail afterwards, and she repeatedly emphasised that her point in this piece was to raise questions, rather than making any particular argument for one side or the other. A press release from the dance company, advertising the show, asks:

“Do we take advantage of what we are familiar with? What takes precedence when faced with individual vs. collective rights?”

Speaking with some friends after the show, none of us felt that the questions had been asked all that clearly in any part of the performance. A few questions were raised through some of the audio clips, many of which were really well selected, but I felt that there was often an unnecessary dichotomy set up between, on one hand, people who wore niqab explaining why they wore it (or why women should wear it), and on the other hand, people who oppose the niqab and who support a ban on it. Not all of the clips fit into this dichotomy, but I would have liked to see more nuance and middle ground: for example, people who might not agree with the niqab itself, but who also don’t agree that it should be banned, or arguments that challenge the idea that niqab necessarily separates people or is necessarily something that should cause discomfort. Or alternate framings of Quebec’s Bill 94 (which I’ve discussed many times already) that look not only at questions of religious freedoms but also at what it would mean to deny services to women who practice their religion in certain ways. It felt like there were a lot of assumptions that could have been questioned much more deeply.

The production was well-intentioned, and not nearly as ridiculous as I initially expected when I first saw the poster. The issue is clearly important to Esmail herself, and I would be interested to see her explore it further. But while the audio in this performance serves as a useful summary of some of the major points of the debate, the performance overall doesn’t bring enough in the way of new questions or perspectives for it to be considered as “risky” or “provocative” as it claimed.