I woke up one morning last week feeling betrayed. I couldn’t pinpoint the source of this overwhelming nausea of deception, but there it was, swimming in the pools of last night’s dinner mixed in with some proverbial bile.

Luckily for my body and eternal salvation, I received a quick diagnosis for those feelings of betrayal by writer Ida Lichter, who recently wrote an article for The Australian, later picked up by The Huffington Post [Religion], entitled “Feminists Betrayed Islamic Women.” In this piece, Lichter laments the shameful silence of feminists – apparently only existent in the Western, non-Muslim flavors – on the atrocities committed against “Islamic women,” specifically in Pakistan and Afghanistan by the Taliban. Lichter complains that the well being of these “Islamic women” (“and homosexuals,” just for good measure) has been compromised by her fellow feminists for the sake of “overarching aims to rid the world of colonialism, neo-colonialism and capitalism.” This apparent commitment to anti-imperialism has left “Islamic women” scarred with the entrails of “Islamist misogyny.”

Okay, just take a minute.

When the United States and allied forces invaded Afghanistan in 2001 and began what would become a disastrous war, a prime justification that was repeatedly voiced by war hawks on all sides of the political spectrum was that the women of Afghanistan needed to be liberated from the misogyny of the Taliban. Very quickly, this reasoning for war was adopted by “Western feminists.” Lila Abu-Lughod, a professor of anthropology, wrote perhaps one of the most important articles on the subject, exploring the question of “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving?” In the article she looks at how Western feminists quickly became war hawks through their sense of entitlement and burden – however earnest at times. Abu Lughod reiterated these points in an interview with the Asia Society, pointing out:

“… The problem, of course, with ideas of “saving” other women is that they depend on and reinforce a sense of superiority by westerners.

When you save someone, you are saving them from something. You are also saving them to something. What violences are entailed in this transformation? And what presumptions are being made about the superiority of what you are saving them to? This is the arrogance that feminists need to question…”

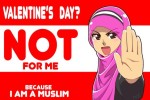

Undoubtedly the situation of women in many countries that we would characterize as “Muslim” is beyond deplorable. Sexual, economic, physical, social and political violence are a common occurrence and must be, without any argument, erased from the experience of any woman – no qualifying noun-adjective necessary. Contrary to the claims of Lichter, there is no shortage of both Muslim leaders and Western feminists denouncing violence against the bodies of Muslim women. The idea that Muslims and Muslim leaders are completely silent on the problems of their community is absolutely absurd and just plain condescending. Not to mention, repeatedly proven false. And even more important there is certainly no shortage of Western feminists carrying the torch of liberation for Muslim women wherever they may be: Idaho or Islamabad. And that is where the problem lies. What Lichter and her ilk miss, and what Abu-Lughod stresses in her discussions, is that there is an industry of saving Muslim women that does not see them in their particulars and only sees a single image and experience that requires correction. This single image and experience has its foil as well in the image and experience of the Muslim man. And what holds the oppressed “Islamic woman” to the oppressive “Islamic man” is the single image and experience of Islam. To echo a famous broken record: this isn’t productive, folks.

Abu-Lughod states in the interview:

“Plastering neat cultural icons like “the Muslim woman” over messier historical and political narratives doesn’t get you anywhere. What does this substitution accomplish? Why, one has to ask, didn’t people rush to ask about Guatemalan women, Vietnamese women (or Buddhist women), Palestinian women, or Bosnian women when trying to understand those conflicts? The problem gets framed as one about another culture or religion, and the blame for the problems in the world placed on Muslim men, now neatly branded as patriarchal.”

Rather than seeing the oppressions of entire populations and their histories, native men and women are pitted against one another in narratives that serve to resurrect age old cultural imperialism. There is no doubt that many, perhaps even most, “Western feminists” have nothing but good intention and earnest concern for the well being of “Islamic women” – but the source, structuring and aims of these sympathies and concerns need closer examination at both the collective and individual levels. It is thus imperative for feminists, who come in more than just “Western” stripes, to acknowledge their own limitations and mortality as well revisit their approach to the experiences, identities and situations of “Other” women.