At Muslimah Media Watch, many of our posts are critical of the way Muslim women are portrayed in various films, literature, and news articles—Muslim women (and other racialised women) are not given the space and time to share their personal stories of struggle and triumph on their own terms. Women’s stories are often mired with assumptions that women’s cultural and religious backgrounds condone the ill treatment they receive from their communities, that their personal experiences of abuse are common narratives to be submissively expected, that the only way women can be “saved” is by an outside member or group’s intervention.

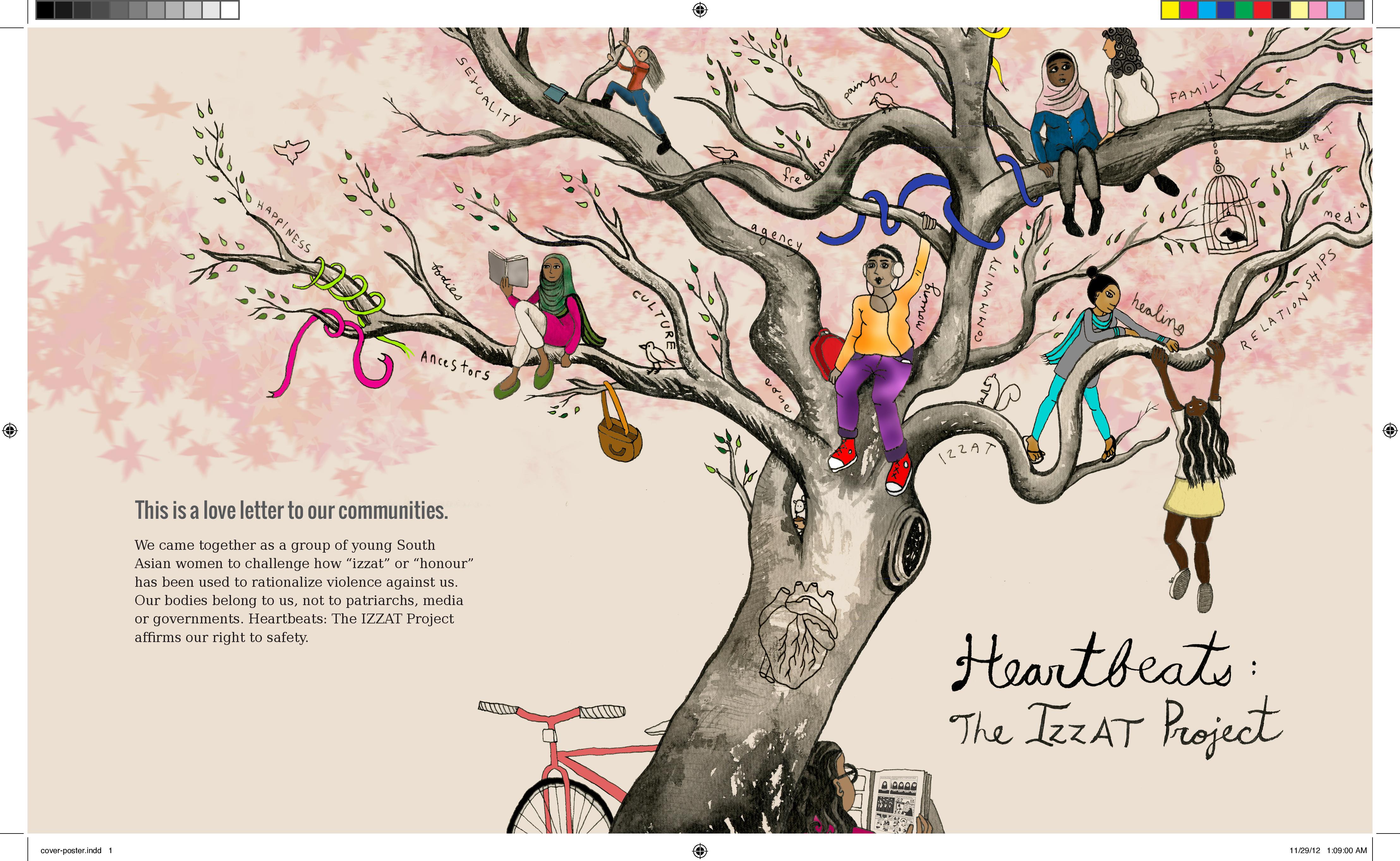

Heartbeats: The Izzat Project aims to give a different portrayal of how young women from the South Asian diaspora living in North America face damaging cultural norms, expectations, and abuse from their communities and families. The compilation of six short stories accompanied by artwork (akin to graphic-novel/storytelling), along with information about how to detect violence and find healing, is a welcome addition to the narratives of South Asian women’s experiences and relationships with their families.

The Izzat Project was an “arts-based workshop” that met in Toronto over the course of six months this year in conjunction with the Pomegranate Tree Group and Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic, which brought South Asian women together “to share stories, heal and participate in arts based workshops.” The storytelling from the workshop was compiled into six stories and illustrated in the Heartbeats comic book.

To begin with, the title of “Izzat” was interesting in and of itself. In Urdu, izzat translates as honor or respect, often with the connotation of a familial honor or respect that is garnered or lost by another’s actions or beliefs. Many of the stories touch on how South Asian families identify their izzat to be of the utmost importance and used to justify abuse towards women who live lives of their own that don’t conform to societal expectations. Maintaining familial izzat is often accomplished through shaming and the abuse of individuals who live on their own terms; the authors of the project address this in their introductory note “to our diverse, complicated, vibrant, funny, fluid communities”:

“When violence happens in our families, we need a different response…not stigma, shame or guilt, but support, understanding and a commitment to change things.

We know that many of us, if not all of us, are survivors of violence, be it physical assault, colonization, racism, sexism, partition, or forced marriage. We believe that our communities can be sites of healing.”

Heartbeats tells the stories of South Asian women from a diversity of cultural and religious backgrounds who encounter resistance from their families for how the women choose to live their lives. Stories address challenges of expectations women face when they move away from home, choose partners of their own, come to terms with their sexuality and discuss sexual abuse, and find their own understanding of spirituality and religious beliefs. Many of the stories address several of the themes at once as women in the stories come to terms with their own identities and beliefs, without supportive family members. A couple of stories are told from the non-human perspectives: a caged bird speaks of how she moves away from her parents home and the compassionate relationship between squirrels and trees over the course of the different seasons.

The portrayals, here, are important in that they allow South Asian women to tell their own stories of overcoming familial expectations and shame of their own identities, and highlight a variety of positive ways to address the adversity in their lives: finding a meaningful personal spirituality, participating in activities that bring them joy, sharing stories of adversity with friends, caring for others, and journaling their lives.

These women’s lives are inherently complicated, as everyone’s lives really are. Women who decide to move away from home, for example, often discuss their own personal conflictions with their decisions—they want to do what is best for themselves while still maintaining ties with their families. In the first story, “The Bad Daughter,” a young woman moves away from home to get some space from her family, whose expectations of her marriage and career decisions have become unbearable: “It’s worth being a bad daughter to clear a path for my future daughters. They won’t have to go through what I did.”

Heartbeats is a wonderful collection—for individuals familiar with South Asian communities or those hoping to learn more about some of the cultural expectations women from those communities may face. The stories allow women to share their experiences and how they address challenging family situations on their own terms and illustrate how women have their own inherent izzat and beauty deserving of community’s support, nurture, and compassion.

You can find more information about Heartbeats: The Izzat Project online here, and you can contact pomegranatetreegroup@gmail.com if you want to order a copy of the comic. For those in the Toronto area, there is a launch of the comic happening tomorrow, December 4, at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Thank you to Pomegranate Tree Group for providing a copy of Heartbeats to review.