For the past two years, sweeping political changes in parts of the Middle East have had a profound impact on socio-cultural and legal traditions. Arab women have been at the forefront of this change, exercising their rights as political citizens and raising their voices against injustices within their own countries and in support of others across the region. Recent developments, however, suggest that while the Gulf states (excluding Bahrain) have remained largely untouched by revolutionary antics, Saudi Arabia appears to have supported credible changes at the policy level which might suggest a softening of attitudes towards women’s role in society. This sudden shift towards affecting democratic change appears to also have spurred increased activism (and civil society engagement) with regards to women’s rights in this conservative country.

One of the most crucial changes to take place is the announcement in 2011 by King Abdullah that women will finally be allowed to vote and run as candidates in municipal elections to be held in 2015. In a country where women navigate public space through an intense system of guardianship founded on a restrictive social code of separation of sexes, this policy announcement is an important step towards political and economic empowerment of women. This announcement occurred several days before the all-male 2011 municipal elections were to take place in the country. Further, potentially spurring this announcement was the “Baladi” campaign, launched in response to women being banned women from voting in the 2011 elections, allegedly on account of lack of institutional preparedness by the government. Independent national ID cards will also be issued to women on the basis of a phased plan, within a seven-year period. This, however, raises an obvious question: how are women expected to “independently” register to vote or stand as candidates in the upcoming municipal elections without the above-mentioned ID cards?

A more recent development this past February was the swearing-in of 30 new female members to the previously all-male Shura or Consultative Council by King Abdullah. It is important to note that Saudi Arabia does not have a written constitution per se or an elected parliament other than a council (Consultative Council) of appointed officials who serve as advisors to the King. A constitution in the form of a Decree (Decree A/90) serves as a framework for legislation, the basis of which is founded entirely in religious jurisprudence. It is no wonder that the appointment of women to an important decision-making and leadership post has been criticized by some clerics. Also joining the council members for the very first time will be female news reporters reporting on Council sessions. Women journalists were previously not allowed to cover these sessions.

Although women are still not legally allowed to drive (despite considerable attempts to the contrary), Prince Alwaleed bin Talal used Twitter to make a case for allowing women to drive, by indicating that such a pronouncement will save approximately 500,000 jobs in the Kingdom. His argument was that allowing women to drive could potentially cut down on the country’s reliance on foreign workers. Whether the aforementioned will actually propel authorities to push to repeal the driving ban is not clear. Other recent achievements include female athletes representing Saudi Arabia at the Olympics in London which despite being criticized by a minority is largely seen as a triumph for women participating in sports in the Kingdom. A ban on female cashiers at supermarkets was also lifted, and women have replaced male sales clerks at lingerie stores across the country.

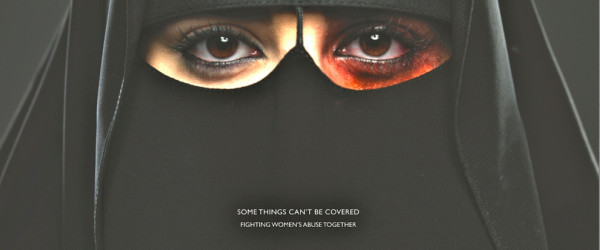

A Saudi ad against domestic abuse. [Source].

Finally, an image posted on Imgur is receiving considerable attention for raising awareness about violence against women. The image (an ad), created by the King Khalid Foundation for their No More Abuse campaign, which depicts a woman in a niqab with a bruised eye, is a stark reminder of the stigma surrounding violence against women. While studies on the nature and extent of domestic violence in the country is limited, a reportby Freedom House indicates that in Saudi Arabia, guardianship laws make it very difficult for battered wives to find shelter. Additionally, the police are not always willing to get involved in what they perceive is entirely private, family matter. Advocacy on reporting domestic violence incidences is a belated, first step towards addressing the lack of legal recourse and support for women under such duress.

Civil society engagement and activism is still comparatively limited within Saudi Arabia (and in many GCC countries except Bahrain). The country hosts numerous CSOs but most are government affiliated and monitored and therefore lack the independence to effectively serve as a counterbalance to the power and influence of the state. Many instances of activism over the past two years however suggest that not only is civil society engagement particularly on women’s rights (which receive considerable media attention) alive and well but has in some respect been influenced by the “uprisings” and “revolutions” taking place across the region. For instance, the Baladi campaign, which I referred to earlier in this post, exemplifies non-violent activism, which may have contributed (the last straw, so to speak) to the increase of women’s political rights in the country. Others, like Manal Al Sharif or the group of women arrested for driving in various cities of Saudi Arabia are part of an even larger number of women hoping to overturn the law that stifles their freedom of movement. Dozens of women have been arrested protesting the incarceration of their male relatives who, as political activists have been held without access to due process for years. Finally, one cannot speak of CSOs without mentioning Wajeha Al Huwaider, the co-founder of the Association for the Protection and Defense of Women’s Rights in Saudi Arabia, an activist and vocal opponent of the country’s guardianship system.

Whether the monarchy is paying lip service to growing civil society discontent, or if these are a series of initiatives spearheaded by a select group of power brokers to manage the country’s image internationally, is unclear. What is becoming increasingly obvious is that Saudi women have joined the chorus of Muslim women’s voices across the region, protesting against oppressive and discriminatory policies both at home and across the region. Ultimately, any legal amendments towards women’s advancement in Saudi Arabia cannot be undertaken without the support of strong government leadership with the political will and commitment to take the necessary political risks (gender being a sensitive issue at best) to implement necessary change. I believe the time leading up to the 2015 municipal elections will be critical in this regard. The purported lack of institutional arrangements which curtailed women’s participation in the 2011 municipal elections will no longer be a valid reason to deny women the right to vote or stand for elections. The signs, however, do suggest that (regardless of the reasons behind them) the present regime is taking measures that will improve women’s role in society, and with the King gaining a reputation for being reform-minded, a golden age for Saudi women could actually be closer than we imagined.