Izzat. It’s Old Rei, the language spoken by Scholars

before the Martials invaded and forced everyone to speak Serran.

Izzat means many things. Strength, honor, pride.

But in the past century, it’s come to mean something specific: freedom.

– Sabaa Tahir, An Ember in the Ashes

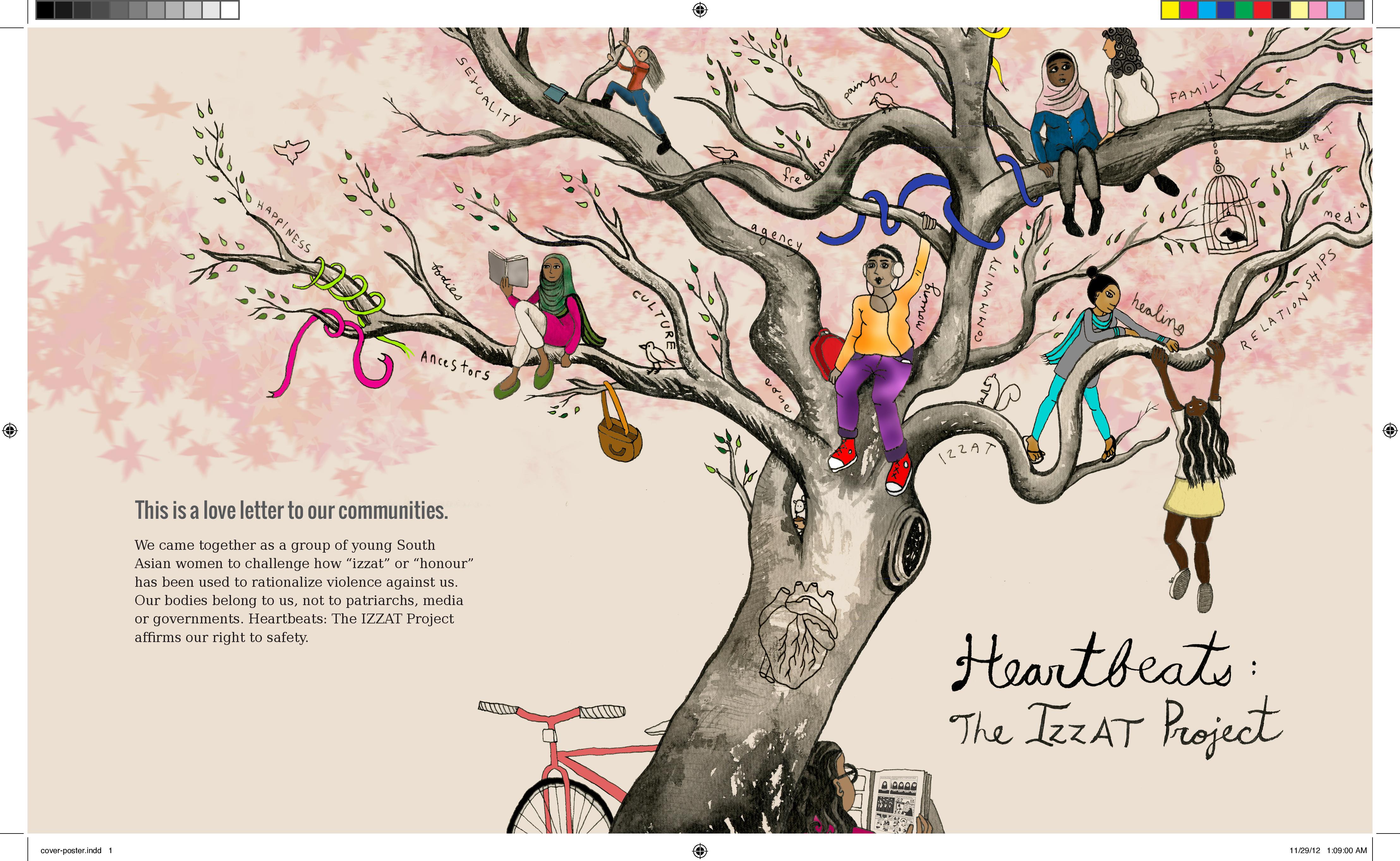

Recently, and in tandem, I read Sabaa Tahir’s An Ember in the Ashes and Lucy Ferriss’ A Sister to Honor. The first, I absolutely loved; the latter, I finished. And while this piece isn’t at all meant to act as a book review for either work, the opportunity to engage in the “fictionality” of each text and what they say about the relationship of honor to womanhood (whether in a fantasy world or in Muslim Pakistan) is an issue that the readings have prompted me to think about. Specifically, this piece hopes to express a discomfort felt around the use of the word “honor” and how it has been conceptualized in relation to Muslim women in media and popular novel productions.

Image via Goodreads.

For its part, An Ember in the Ashes is set in a world inspired by ancient Rome. The heroine is the slave Laia, who risks her life to try and save her brother who is arrested by the Empire. The hero is Elias, a soldier of the Empire, who only wants to escape from its despotic grip. Their intentions and their worlds converge in this young adult novel that has been a standout in a year of really outstanding YA novels. Indeed, Tahir’s storytelling captivates and the fantasy setting she creates is wonderfully rendered -I couldn’t put it down and have recommended it to students and friends who felt the same way. Of course, different readers will take away different things from the same books and I don’t want to spoil it for anyone who has yet to read it, but what I really appreciated in this one was the sense of nostalgia and honor it seems to want to examine while not shying away from an exploration of what the subjugation of peoples and cultures might entail. There is the way in which Tahir has Elias raised amongst indigenous Tribesman and Laia belongs to the once learned Scholarly clans who may or may not have “sold out” to the Empire. There seems then to be a sort of political allegory at work in the novel. Furthermore, Laia’s subjugation is a gendered one: her place as a slave girl means that she can be objectified, used, and raped by men of the empire without question. Still, Laia’s strength of character grows and time and again she demonstrates her courage and her honor (read: honor as strength of character or adherence to moral principles) in how she perseveres to save her brother and how she treats the friends she makes while on her mission.

Image via Goodreads.

Lucy Ferriss’ A Sister to Honor also features a brother and sister relationship at its core. Pakistani student Shahid Satar is the rising squash star at a New England university who is charged with the protection of his sister Afia, studying medicine at a nearby campus. Things start going horribly wrong when a picture of Afia holding a boy’s hand surfaces online and their step-brother insists that Shahid right the dishonor she’s brought upon their family. Intertwined with this pretty typical look at honor as envisioned in the Muslim world (I’ll unpack this claim momentarily) is the character of Lissy, the squash team’s kick-butt female coach. Described as tall with spiky blonde hair, when we first meet Lissy, she’s giving her team the “honor talk” (pg. 13). Immediately recognizable in Lissy is the white saviour complex and Ferriss’ construction of honor as something better understood in the liberal Western context as opposed to its ignorant and misguided notion in the Eastern, Muslim world. Throughout the tale, Lissy’s dedication to her players is unflinching, and when Afia is in trouble, it is Lissy (of course) who risks everything to keep her safe. I stated earlier that I did finish the work, something that I felt was quite a feat mostly because the opening scene was, to me, very much an exaggerated (and unrealistic) notion of how Muslim women view the onset of womanhood through the onset of the menstrual cycle. Indeed, the novel begins with Afia’s mother, Farishta, going about her household duties while contemplating her children in the US and her daughter Sobia. Farishta has found Sobia’s “bloodstained panties” and would have to explain to her “as she had explained to Afia seven years ago, as her own mother had explained to her when this awful-seeming thing happened – that a new and wonderful burden was laid upon her…[that] she would walk with a new, firm carriage, protecting the treasure of her womanhood” (pg. 6).

In any case, I have, in my discussion of these two novels, conflated their genres: Ferriss’ work is supposed to be realist fiction; Tahir’s work is fantasy. And maybe it is the genres that make for a stronger reaction: realist fiction is supposed to give us a sense of life as it is lived; fantasy is supposed to distance us in order that we might contemplate life as it may be. That Ferriss’ narrative so easily falls into the trope of Muslim girl brings shame on her family and must therefore be killed is troubling to me – not because I’m trying to deny that such atrocities happen – but because it’s almost always true that when the word “honor killing” is used in the media it is typically in relation to the murder of Muslim women. And this is frustrating. MMW has talked about this before too (see: here and here for examples). Furthermore, it’s head-scratching when we think about how family violence, if it occurs in non-Muslim contexts, is represented; “honor” rarely comes into the picture. It might be anger, jealousy, or some other generally negative emotion – so why then place what might be construed as a positive force like honor onto Muslim contexts thereof and why the etymological shift in the very meaning of the word? Indeed, there isn’t anything honorable about murder; and while we’re on it, there’s isn’t anything Islamic about it either. But, google the term “honor” by itself and then add the words “Muslim woman” to it. Note the difference. If we’re going to critique the dichotomy, then we’d do well to embrace the type of nuanced rendering that honor is given in a work like Tahir’s An Ember in the Ashes and problematize the sort of typical and prejudiced depiction of it in a work like Ferriss’ A Sister to Honor.