Four years ago I wrote “How are Muslim Women doing in Political Cartoons,” a piece that analyzed the use of gendered and islamophobic language in Anglophone political cartoons. At the time, I was writing my undergraduate thesis, which focused on media coverage of First Ladies in Mexico, particularly in political cartoons. Later that year, I attended a Religious Studies conference at Lethbridge University, where I presented an extension of this particular piece. As fun as my presentation was, (because, hello! cartoons?), I found resistance.

For some scholars of religious studies, cartoons, as a medium, are not a legitimate source of analysis because they represent “personal opinions” rather than wider social discourses. What is more, because of this, some believed that Muslim women should not “feel offended” by depictions of themselves in art, cartoons and the media, because these “opinions” remain opinions and that is that. Such an attitude was, in my view, not only problematic in terms of being told how Muslim women should feel, but also because they place boundaries around what kind of discourses should be subject to analysis.

However, if there is something that my thesis process showed me, it is that cartoons influence and are influenced by the author’s surroundings, biases and “blind spots;” that these images become a source and a form of discourse the moment they touch the public sphere and that the imagery has tangible effects in society, whether it is voter-swinging, fear, violence, etc. Political cartoons are simultaneously communicators and reflections of public opinion. And as our U.S. neighbours are currently going through an election (one that has the world terrified, as sad as it sounds), there are some lessons to be learned from Canada’s own political tactics during the country’s last election.

Since the fall of 2015, Muslim women and the niqab issue have featured heavily in the Canadian political scene. Not only were niqabis used to make political commentary on immigration, but they were at the forefront of discussions on what it means for Canada to be a “nation of immigrants” (something that weighs heavily on Indigenous sovereignty, I must say) and to be a truly “multicultural” society.

The imagery of the oppressed niqabi has strong ties to colonial discourses on women and minorities. If you are ever interested in finding out more about how stereotypes and imagery are closely tied to issues of colonial violence, I would recommend turning to Kim Anderson’s A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood. Anderson is a Cree/Métis scholar, and she shows how the image of the “Indian Princess” (i.e. Pocahontas) and that of the “Indian squaw” were used to justify the colonization of the Americas and perpetuate violence against Indigenous women. On the one hand the Indian princess was welcoming to the white colonizer and accepted his unquestioned superiority. On the other hand, the Indian squaw was used to “show” and “prove” everything that was wrong with “uncivilized” Indigenous communities and justify why the colonization and Indigenous peoples was necessary. Women and third gender peoples were often at the forefront of this dynamic.

Anderson shows that the dynamic has changed a little, but it is not gone. The image of the “Indian squaw” is still pretty prevalent, and the fact that there are thousands of unaccounted for missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada demonstrates the tangible effects of imagery and discourse in making Indigenous women dispensable beings.

There’s a similar dynamic when it comes to immigrants from the “third world.” Canada has had for a long time a “right type of immigrant” and a “wrong type of immigrant.” What constitutes “right” or “wrong” has changed over time, but there is a commonality. Just as the “good immigrant” is all about the assimilation, integration and adoption of “Canadian values,” the “bad immigrant” (just like the Indian squaw) justifies the implementation of racist immigration policies along with the economic, military or developmental interventions in other countries. Immigration policies, for instance, have discouraged at different points in time the immigration of non-white people, polygamous families, Sikh, Chinese, and countless others. In addition, LGBTQ people were considered an “inadmissible class” and HIV positive individuals are often discriminated against. Muslims, particularly in recent years but not only now, have been perceived with a lot of suspicion. Whereas 9/11 and the occupation of Afghanistan had a lot to do with that, Canada has had its own share of complex issues with racism, sexism and Islamophobia that have been transplanted onto imagery around Muslim women.

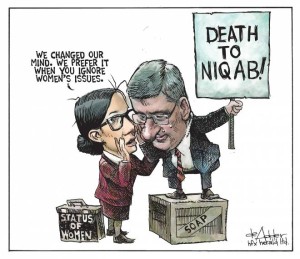

During the election time, this became extremely obvious. It did not matter if it was the Conservative, Liberal or NDP party addressing the issue, what we got was the debacle of three white male candidates debating the niqab. The niqab has a very recent political history in Canada. Provincial and federal governments have prevented survivors of sexual abuse to testify against their abusers in their niqab and they have tried to prevent Muslim women from taking their citizenship oath while wearing the garment, and cases of discrimination, harassment and violence are not unheard of.

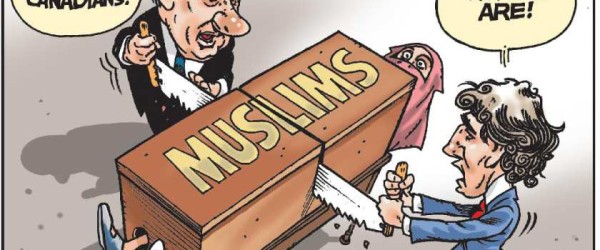

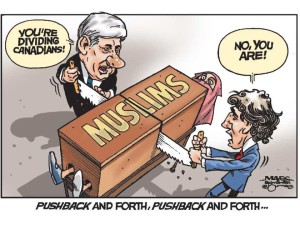

Numerous political cartoons used the image of the niqab to critique politicians, particularly to shame ex-Prime Minister Stephen Harper, while using the garment as the representation of Muslim women. But let’s also point out that in the majority of cartoons, Muslim women appear to be silent, agency-less, oppressed or powerless in order to achieve the comical effect. I have yet to see cartoons in mainstream Anglophone papers that depict Muslim women with some kind of agency.

These portrayals are heavily influenced by, first, mainstream Canadian ideas around women of colour and women from the Third World as oppressed by their own men (i.e. something that has been reaffirmed through cases of “Honor Killings” such as the Shafia case). Next, by the idea that Muslim women are inherently the “other,” and it does not matter if you are an immigrant, a refugee or a First Nations convert. And finally, by the power dynamics of white male privilege, which asserts itself over women of colour by policing their choices, establishing institutional racism and having public debates about issues that should, in plain terms, be of no concern to them, such as the niqab.

Even when Muslim women have acquired more access to media, the reality is that we are pretty far away from the policy-making process at the government level (very few Muslim women and social justice activists have access to the top). So Muslim women’s voices can be selectively heard and selectively ignored. Political cartoon artists’ during the election made a point not only of showing how Muslim women were being silenced, but silencing them themselves by making them invisible, powerless of stereotypically in different ways. For instance, Muslim women do not speak in the cartoons; they are pitiful in a way, particularly as it relates to the Syrian refugee crisis; they are depicted purely as a piece of clothing; and they are often “handled” by the, often, white males in positions of power.

The problem is that the discourse on Muslim women in the media, including in political cartoons, informs the public’s view on what Muslim women’s “place” is or should be in Canadian society. Post-October 19, the day of the election, Muslim women and women of colour mistaken as Muslim continued to make it into the news after being attacked in a surge of Islamophobia following the Paris attacks. In many of these cases the hijab (or something looking like it) became the primary way in which these women were harassed.

I do think there is a responsibility in issues of representation. We cannot pretend that a good joke is just a joke and does not have tangible effects when it feeds into discourses of exclusion. There is a responsibility in creating images and in portraying Muslim women in certain ways, just like as observers there is accountability in critically examining these images.

1 Comment

[…] not immigrants, they were settlers. And they took over lands and created policies that stipulate the “right” type of immigrant and the “wrong” type of immigrant. For a while, the right type was white, straight and from certain countries in Europe only. This […]