This post was originally published on the writer’s blog.

I left the mosque many years ago. I think the last straw for me was seeing female teachers and preachers telling us that women should not be in positions of leadership; that they should stay home and care for their children; or that a woman’s nature is _____________ and therefore, she does not belong in the public sphere. One day I just walked away and did not look back.

Yet, once in a while I feel guilty. I think to myself, mosques remain community centers with a lot of power. If they are to change, we need to be committed to actually shaking up the broken structures. Thus, every so often, and as my own acts of self-care allow, I go back to the Sunni mosques in my area and volunteer to bake, to teach, to help… In doing that, I have had to develop a thick skin and a high tolerance for misogyny, violence and other people’s patriarchal practices.

But last year the mosque pushed me away once more. When my partner died, I was denied space to mourn. “That’s not Islamic,” “But we don’t accommodate mixed congregations,” “We can’t have non-Muslims” (a.k.a. my parents and brother), “Sister, that’s shirk.” That was my family’s first encounter with Muslims and the mosque environment… and God, I hope, it will be last one!

However, I was not surprised… I knew what I was up against.

Needless to say, I was once more unmosqued. In my frustration trying to find a sheikh that would recite some prayers for my partner, I said to the very last sheikh I spoke with, “Your dawah is garbage. I do not know what the point of conversion is, if every single time I have needed anything as a convert the answer has been no.” The sheikh thought I was harsh…

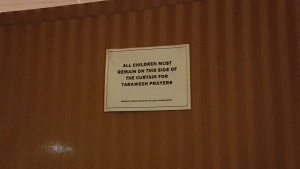

Sign at Assunah Muslims Association in Ottawa. Source.

Since these events, I had not been back to the mosque. Nonetheless, this Ramadan I decided to go back. You’ll see, I have a soft spot for sacred spaces. I think they have so much potential for beauty, growth and spirituality, and, to some degree, I think that they have great potential for civic and participatory democratic engagement.

Hence, Stephanie, who is the author of Love God Diversity and a close friend of mine, and I visited all the mosques in our city. We ate a lot of iftars and prayed a lot of tarawih. We were welcomed in some and treated with suspicion in others. We were shocked by the sobriety of the majority of Sunni women spaces in comparison to the cheerfulness of some Shi’a mosques and Sufi settings. But above all, we were reminded that being a woman in the mosque is not easy business.

If you follow my work on Muslimah Media Watch, you know that the writers have tirelessly recorded their experiences of the mosque. Some topics have included male-focused mosques, ableism, the silenced voices of Muslim women and all-women spaces. Similarly, projects like Side Entrance, that are not unique but have been quite successful in showing the discrepancies between men’s and women’s prayer spaces, have flourished. Recent films like Unmosqued have also attempted to explain why so many youngsters, including women, drop out of the mosque. So the challenges are not just in our imagination.

Assalam Mosque Ottawa- Tarawih Prayers. Source

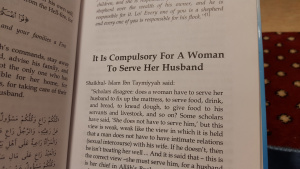

My friend and I had similar experiences to the ones recorded by these writers and filmmakers, and throughout our “social experiment” our identities as converts, as young feminists and as women were constantly challenged. In less than thirty days, my friend walked out of a mosque where a partition was raised during iftar (in a mosque where this had never been the case); we were confined to basements without ventilation or working fans; we were shoved with the kids (because you know, women=kids); we had to jump through puddles of dirty water in bathrooms and dodge smelly garbage bins on our way to the women’s section; we were lectured about “proper clothing” and “proper” shoulder-to-shoulder formations while praying; we were expected to tell emotional convert stories to amuse other congregants; we were continually questioned about our ethnic backgrounds; we attended university iftars where the men that usually have “normal” interactions with us, would not even look us in the eye, let alone say hi!; we were thrown into “family sections,” where we were forced to sit with other people’s husbands and children, but not allowed to sit with the single men; we sat through hours of Arabic speeches with no translation to English or French, the official languages of Canada; and the cherry on top? We picked up some literature at some of the mosques promoting marital rape and violence against women.

From the book “Marital Discord: Causes & Cures” By Majdi Muhammad Ash-Shahawi. Source.

So what do you do when you feel so undesired?

I must say that the answer for me has been alternative grassroots spaces. I am not sure if perhaps is the fact that the mosque model is outdated, or if it was never functional to start with. I can’t tell if it is because institutional Islam, just like any other political or religious institution, is built on power relations that are often racialized and gendered. Or if maybe it is me being “emotional” as one Reddit reader told me in a private message, after reading a piece I wrote titled “Decolonizing the Mosque.”

However, what it comes down to is that the people who have been there for me and for my spiritual growth, do not have fancy buildings with crappy women’s sections. They can’t afford to feed hundreds of people, so instead they organize potlucks and focus on the spiritual fulfillment that we bring to each other from socializing and praying together. And above all, we are concerned with each other’s well-being rather than the legalities and bureaucratic shapes of the religion.

Will I go back to the mosque? Sure, I will probably end up going at some point to remind myself of the importance of having alternative spaces. Will I stay? I doubt it. The undesired need to continue building their own safe spaces.

For those in Canada, some grassroots alternative spaces include the following (if you know of some others, drop me a line):

1 Comment

“I am not sure if perhaps is the fact that the mosque model is outdated, or if it was never functional to start with.”

The “mosque model” was instated by the Prophet. Whatever it has morphed into, it’s pretty disrespectful to insinuate it wasn’t functional.

Where I live, we have mosques where single mothers find support, where older aunties learn the meaning of the Quran as they have always yearned to. We have mosques where the women’s spaces were built with the intention of being musallahs, so that women are included at all times of the month. We have mosques that enable undocumented asylum seekers to have food and shelter.

I’m really sad you didn’t find the support at your mosque, that so many other people have. But the totality with which you write your article reminds me very much of the point made in this one: http://www.vice.com/read/islam-for-xenophobes